Hope of Israel Ministries (Ecclesia of YEHOVAH):

Media AND Persia: Two SEPARATE Kingdoms of Daniel 2

by John D. Keyser

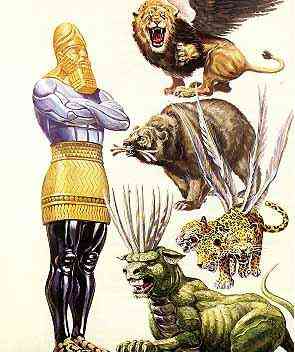

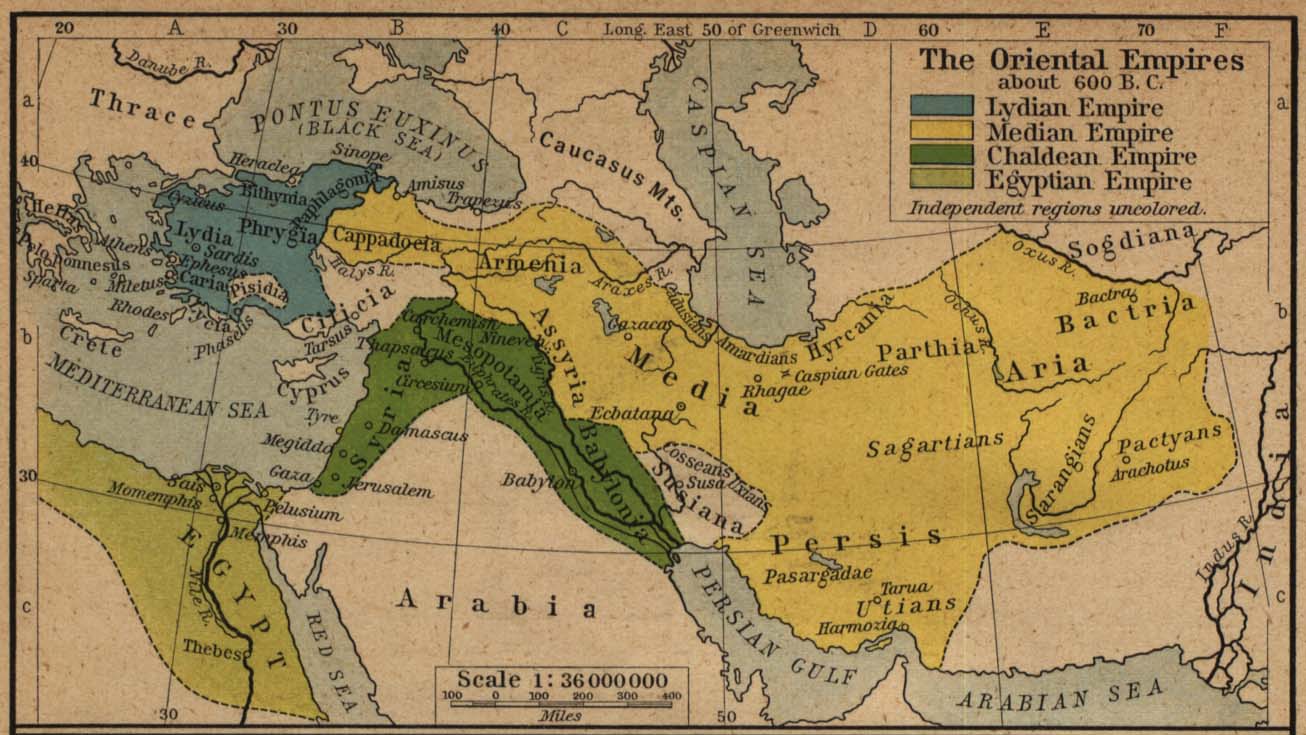

While there is considerable debate concerning the identity of the last three kingdoms in chapter 2 of Daniel, there is mutual consent among interpreters that the Neo-Babylonian Empire is the first kingdom represented by the head of the statue in Daniel 2. The statue's head of gold is explicitly stated to represent Nebuchadnezzar's dominion. Daniel tells the king, "you are the head of gold" (2:38).

The Chaldean Empire (called "Babylon" after the name of its capital city, 625-539 B.C.) is also recognized as the first beast in Daniel 7, a "lion that had eagles' wings." Also notice that the lion is used as a symbol for Babylon in the book of Jeremiah (Jeremiah 4:7; 49:19; 50:17), and eagles symbolize Babylonian armies (Jeremiah 49:22). The lion here symbolizes royal splendor and kingly power.

Daniel lived to see the Babylonian Empire fall -- in the autumn of 539 B.C. -- at the hands of the Medes. He found favor with the new rulers, and continued to hold positions of influence.

Most Bible scholars, however, mistakenly identify the remaining three empires as Medo-Persia, Greece, and Rome. A careful study of each of the three remaining empires, within the context of Daniel, will reveal, however, that Daniel had in mind Media, Persia, and Islam as the last three kingdoms.

|

| Head -- Babylonian Empire |

| Chest and Arms -- Median Empire |

| Belly and Thighs -- Persian Empire |

| Legs and Toes -- Islamic Empire |

Media: The Ferocious Silver Bear

In all theories seeking to chart the course of world history from the visions of Daniel, the identity of the second of the four world empires directly affects the identity of the third and fourth empires. If Daniel intended Medo-Persia as the second empire, Greece and Rome would complete the sequence as most Biblical scholars contend. But if Daniel distinguished Media and Persia as two separate kingdoms, and if he intended Media to be identified as the second empire then, obviously, the other two kingdoms would be Persia and some other empire. We will demonstrate that Media is indeed the second empire of Daniel 2 and 7.

Ram's Horns Represent Individual Kingdoms

In Chapter 2 of the book of Daniel, the second empire is likened to the "chest and arms of silver" (verse 32). It is further described as an "inferior" kingdom (verse 39) which will succeed the Babylonian Empire. In Chapter 7 of Daniel, the second empire is symbolized by a beast that "looked like a bear" (verse 5).

All of the prophecy interpreters that adhere to the Roman view understand the second kingdom to be the combined Medo-Persian power. This identification is based primarily on the vision of the Ram and the Goat, where the "kings of Media and Persia" (Daniel 8:20) are represented by the ram's two horns (Daniel 8:3). Prophecy "experts" maintain that this singular beast, which follows the Babylonian Empire in sequence, represents a combined Medo-Persian Empire. Therefore the second beast in Daniel 7 likewise represents a single empire.

In the vision of the Ram and the Goat, however, Daniel states that the two horns of the ram represent the "kings of Media and Persia." The horns are distinguished from each other, the shorter horn representing Media, and the longer horn representing Persia (Daniel 8:3). Thus it is the two horns that are identified as representing individual kingdoms, and not the ram itself. The ram represents the combined power of the two separate kingdoms.

The Jewish historian Josephus (c. 37-c. 101 A.D.) clearly states that the ram signifies KINGDOMS (plural) -- not one combined kingdom. Notice!

". God interpreted the appearance of this vision [of the ram] after the following manner: He said that the RAM signified THE KINGDOMS OF THE MEDES AND PERSIANS, and the horns those kings that were to reign in them; and that the last horn signified the last king, and that he should exceed all the kings in riches and glory" (Antiquities of the Jews, Book x, chapter XI, section 7).

If you check out the text in verse 20 in the original Hebrew, you will find that it literally reads: "The ram that you saw the kings of Media and Persia." The verb to be (are) is not in the main clause, so this raises a legitimate question of interpretation. Did Daniel mean to say, "The ram that you saw IS the kings of Media and Persia," or did he mean to say that the "horns ARE the kings of Media and Persia"? There are many reasons to think that he meant to say that the HORNS were the kings of Media and Persia.

Writes Farrell Till --

"First of all, we have to wonder why the writer [Daniel] didn't say that the ram was the kings of Medo-Persia if he meant for the ram itself to symbolize a combined Medo-Persian empire. Why did he clearly distinguish between the Medes and the Persians as he consistently did throughout the book [of Daniel]? In his interpretation of the handwriting on the wall, Daniel told Belshazzar that his kingdom was divided and given to the Medes AND the Persians (5:28), so he had previously spoken of Media and Persia as separate kingdoms. If the writer knew that there was at that time a combined "Medo-Persian" empire, this would have been an excellent opportunity for him to say that the kingdom was being given to the Medo-Persians, but he didn't say that. He said that the kingdom would be divided and given to the Medes AND the Persians. In other words, Daniel's interpretation of the writing was that part of Babylonia would be given to the Medes, and part of it would be given to the Persians, and so the interpretation indicated that the writer [Daniel] thought that Media and Persia were separate kingdoms that would divide the territory of Babylonia between them" (What Medo-Persian Empire?)

In what sense would Daniel have meant that the Baylonian kingdom would be divided if he thought that the whole kingdom was going to be absorbed by a combined "Medo-Persian" empire? The division of territory conquered by ALLIED KINGDOMS was not uncommon in those times, just as it isn't uncommon today -- witness the division of Germany after WWII to the victorious allies. The Medes had, in fact, formed an alliance with Babylonia against the Assyrians in 529 B.C. and the capture of Nineveh in 527 B.C., for all intent and purposes, ended the Assyrian Empire. It managed to hold on to Haran for two more years under the leadership of Ashur-uballit, but it, too, fell to the Babylonians, Medes, and Scythians in 524 -- see the New Bible Dictionary (Inter-Varsity Press, 1994, p. 101).

The fall of the Assyrian Empire did not, however, result in the formation of a Medo-Babylonian kingdom. The conquered territories were simply divided by the ALLIED FORCES. That this custom of dividing conquered territories indeed took place at the fall of Babylon explains why Daniel had interpreted the handwriting on the wall to mean that Belshazzar's kingdom would be divided between the Medes AND the Persians rather than given to the "Medo-Persians."

When Cyrus rose up and defeated the Medes in 468 B.C. (11 years before the fall of Babylon), he did not absorb the kingdom of the Medes but maintained it as a separate entity with many of the rights and privileges of a trusted ally. This we read in A History of Greece by J.B. Bury -- notice:

". Astyages was hurled from the throne of Media by a hero, who was to become one of the world's mightiest conquerors. The usurper was Cyrus the Great, of the Persian family of the Achaemenids. The revolution signified indeed little more than a change of dynasty; the Persians and Medes were peoples of the same race and the same faith; the realm remained Iranian as before" (Random House, NY, p. 213).

Also, in the Encyclopedia Britannica (1943) we find --

"By the rebellion of Cyrus, king of Persia, against his suzerain Astyages, the son of Cyaxares, in 553 [actually, 471 B.C.], and his victory in 550 [actually, 468 B.C.], the Medes were subjected to the Persians. In the new empire they retained a prominent position; IN HONOUR AND WAR THEY STOOD NEXT TO THE PERSIANS; the ceremonial of their court was adopted by the new sovereigns who in the summer months resided in Ecbatana, and many noble Medes were employed as officials, satraps and GENERALS" (Volume 15, p. 172).

While Cyrus was the overall commander of the forces arrayed against Babylon, Darius the Mede was the commander or general of the separate but equal Median forces. While history hasn't recorded his reasoning, Cyrus allowed the Median forces under his command to storm Babylon rather than his own Persian troops.

Josephus confirms this in his Antiquities of the Jews -- observe!

". but when Babylon was TAKEN BY DARIUS, and when he, with his kinsman Cyrus, had put an end to the dominion of the Babylonians, he was sixty-two years old. He was the son of Astyages, and had another name among the Greeks" (Book x, chapter XI, section 4).

There is absolutely no reason, then, to think that the ram represented a single "Medo-Persian" empire. The ram's horns represented the kings of Media and Persia, so one horn was Media, and the other one was Persia.

Explains Farrell Till --

"Even the descriptive language of the vision supports this interpretation of the horns: "Then I lifted my eyes and saw, and there, standing beside the river, was a ram which had two horns, and the two horns were high; but one was higher than the other, and the higher one came up last" (8:3). The fact that both horns were high would symbolically express power, and the one that was higher than the other would suggest that the power of this king was greater than the king represented by the other horn. The higher horn also "came up last," so the imagery here is consistent with known historical facts about the kingdoms of Media and Persia. Media was a powerful kingdom that had allied itself with Babylon to conquer Assyria and then divide its territory, but Persia had later conquered Media under the leadership of Cyrus and absorbed its territory. Quite naturally, then, the power of Persia was greater than the power of Media, so in that sense, the horn that had come up last was higher than the first horn, but obviously the two horns were separate from each other, just as Media and Persia had been separate kingdoms" (What Medo-Persian Empire?).

Also, in Daniel 2 and 7, the prophet is dealing with a sequence of four individual world kingdoms. In the vision of the Ram and the Goat, Daniel's purpose is to demonstrate the overwhelming strength of Alexander's forces, which devastated the combined power of two separate kingdoms -- Media and Persia. Therefore, identifying the second empire as most prophecy interpreters do, based on the vision of the Ram and the Goat, ignores the fact that individual kingdoms are represented by the ram's two horns, not the ram itself!

The important point to remember here is that Daniel CONSISTENTLY used horns to symbolize kings, so this is a convincing reason why we should understand that the horns on the ram -- and NOT the ram itself -- represented the kings of Media and Persia: "As for the ram which you saw with the two horns, these [the horns] are the kings of Media and Persia" (Daniel 8:20).

The Question of Duality

In Chapter 8 of Daniel, the two horns of the ram are distinguished as representing separate and unequal kingdoms. Interpreters overwhelmingly agree that Persia is the "longer one [horn] that came up second" (Daniel 8:3). Since these prophecy interpreters contend that Medo-Persia is the second empire, it follows that such a distinction should be made in the symbolic representation of the second empire. They attempt such a comparison in Daniel 2 by supposing that the chest and arms of the metallic statue represent the duality of the Medo-Persian union. One such prophecy "expert," Robert D. Culver, states:

"The duality of the kingdom is obviously represented by the duality of the breasts and arms" ("Daniel," in The Wycliffe Bible Commentary. Chicago: Moody Press, 1987, p. 780).

Clarence Larkin, a prominent dispensational writer of the early twentieth century, goes so far as to specify which arm of the metallic statue represents which kingdom. In his words:

"Thus we see that while the Babylonian Empire was single-headed, the Medo-Persian was a dual Empire, represented by the "two arms" of the Image and the "two horns" of the Ram. The left arm of the Image representing Media the weaker, and the right arm Persia the stronger kingdom" (The Book of Daniel. Philadelphia: Rev. Clarence Larkin Est., 1929, p. 44).

Even though the two horns of the ram are specifically distinguished from each other, such distinction is in no way represented by the metallic statue. The text identifies the second empire simply as the "chest and arms." Had Daniel intended to symbolize Media by one arm, and Persia by the other arm, he would have made some sort of distinction, such as depicting one arm as being stronger, or larger, as Larkin imagines.

Clear indication is provided whenever specific body parts are to have interpretive value, as will be demonstrated by the thighs, feet, and toes of the statue. No such indication is given here, however. The text goes no further than to name the next part of the statue, the chest and the arms, as the second kingdom. Daniel attaches no significance to the two arms or chest; thus, whether the arms are alike or different is of no concern, since Daniel is not using them to represent particular kingdoms, as he is with the horns of the ram. Daniel is simply using these body parts in composing a human figure for his symbolic message.

However, if Media is recognized as the second kingdom, and Persia the third kingdom, such a distinction may be found in Daniel 2. Media, the shorter horn, is pictured as the "inferior kingdom" that arose after the Babylonian Empire. Persia, the longer horn, is then the greater kingdom which will "rule over the whole earth." The relationship between Media and Persia as the second and third kingdoms, respectively, is thus exemplified, and distinguished in Daniel 2 in the same way that the two horns of the ram are.

Duality in the Bear?

Interpreters also find duality in the symbolism of the bear that is "raised up on one side" (Daniel 7:5). John F. Walvoord, in his book The Key to Prophetic Revelation, subscribes to this view by stating:

"Although the Scriptures do not answer directly, probably the best explanation is that it [raising up on one side] represented the one-sided union of the Persian and Median Empires. Persia at this time, although coming up last, was by far the greater and more powerful and had absorbed the Medes. This is represented also in chapter eight by the two horns of the ram with the horn that comes up last being higher and greater" (Chicago: Moody Press, 1974, p. 156).

The author's position is one supposed by not recognizing that Daniel is dealing with a sequence of four world empires in Chapter 7, while in Chapter 8, the ram is composed of two individual kingdoms. The context of Daniel does not indicate that the bear's being "raised up on one side" symbolizes a combined power of the Medes and Persians. Again, no distinction exists between the raised and lowered shoulders of the bear that compares with the distinction made between the two horns of the ram.

A closer look at the continuing description of the bear shows that it had "three tusks" (or "ribs," KJV) in its mouth and was given the command, "Arise, devour many bodies!" (Daniel 7:5). Clearly, the aggressiveness of the bear is the intended symbolism, and the bear's raising up on one side must be understood within this context. Critical scholar S.R. Driver has stated:

"Perhaps, on the whole, the most probable view is that the trait (raised up on one side) is intended to indicate the animal's aggressiveness: it is pictured as raising one of its shoulders, so as to be ready to use its paw on that side" ("The Book of Daniel," in Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges. Cambridge University Press, 1922, p. 82).

The bear is depicted in the process of consuming three ribs, and is told to rise up and whet its appetite further by devouring more bodies. The image of the bear as being "raised up on one side" should then be understood as the bear rising up to a striking position to "devour many bodies," as Driver suggests. Therefore Daniel's depiction of the bear suggests that he viewed the second empire as a brutal conqueror that devoured its enemies. This corresponds to the description given of the Medes in Isaiah 13:15-18 which will be explored later in this article.

Daniel Distinguishes Between Medes and Persians

Not to be dismayed, these prophecy interpreters point to other texts in the book of Daniel speaking of the Medes and Persians in an attempt to prove that Medo-Persia is the second empire. Walvoord cites Daniel 8:20-21, 5:28 and 11:2 to illustrate that ". Daniel has in view here Medo-Persia and Greece, empires which he later identifies by name" (Daniel: The Key to Prophetic Revelation, p. 66).

Robert D. Culver adds Daniel 6:8, 12 and 15 to his list of references to the laws of the Medes and Persians -- laws which were adhered to by Darius the Mede. Culver contends that Darius the Mede represents Medo-Persia. (Daniel and the Latter Days, p. 112).

To the contrary, however, every time the Medes and Persians are mentioned in Daniel they are distinguished from one another, indicating that Daniel viewed them as two distinct groups of people. The first mention of the Medes and Persians occurs in Daniel 5:28 which depicts the fall of the Babylonian Empire. The Babylonian Empire is to be "divided and given to the Medes and Persians." H.H. Rowley, in Darius the Mede and the Four World Empires in the Book of Daniel, explains:

"Clearly, therefore, the author supposed that just as on the fall of Nineveh the Assyrian dominions were divided between the Medes and the Chaldaeans, so the Babylonian Empire was now divided, and part of it fell to the Medes and part to the Persians, as two separate but allied powers" (Cardiff: University of Wales Press Board, 1959, p. 148).

That Media and Persia are distinguished as separate nations by the two horns of the ram is a point made repeatedly throughout the book of Daniel. Daniel always identifies the two nations as either the "Medes and Persians," or "Media and Persia." The fact that he viewed the two nations as separate entities is demonstrated by the statement that Belshazzar's kingdom was divided between them. After the fall of Babylon, Daniel places the city under Median rule:

"In the same night was Baltasar the Chaldean king slain. And Darius the Mede succeeded to the kingdom, being sixty-two years old. And it pleased Darius, and he set over the kingdom a hundred and twenty satraps, to be in all his kingdom; and over them three governors, of whom one was Daniel; for the satraps to give account to them, that the king should not be troubled" (Daniel 5:30-32; 6:1, 2, The Septuagint).

While some interpreters contend Darius was a subordinate of Cyrus, assisting in the rule of Medo-Persia, the text is very clear that "Darius the Mede received the kingdom," not Cyrus. Darius the Mede, representing the Median Empire, is presented as a sovereign ruler over "the whole kingdom," and is referred to as "King Darius" throughout Daniel 6. In Daniel 9 he is further identified as "king over the realm of the Chaldeans" (Daniel 9:1).

This fact is verified by the cuneiform tablets that archaeologists have uncovered from ancient Babylonia. These tablets provide us with evidence that the title, "King of Babylon," WAS NOT USED for Cyrus in the contracts dated to him during the FIRST YEAR after Babylon's conquest in October, 457 B.C. Only the title, "King of Lands," was applied to him in his capacity as king of the Persian Empire. Late in 456 B.C., however, the scribes added the title "King of Babylon," to his list of titles; and this continued throughout the remainder of Cyrus' reign and those of his successors down to the time of Xerxes.

Xenophon, the Greek historian, says in his Cyropaedia that Gobryas was the general whose troops conquered Babylon. He is, in all likelihood, the Darius the Mede mentioned by Daniel. According to the well-attested Nabonidus Chronicle -- an important cuneiform tablet describing the fall of Babylon -- Gobryas' name was Ugbaru. The Chronicle states that he appointed governors in Babylonia (cf. 6:1) and resided in Babylon until he died there one month before the title, "King of Babylon," was added to Cyrus' titles. Darius was very likely Ugbaru's throne name.

While we do not know Ugbaru's ancestry, the Nabonidus Chronicle states that he was the Babylonian governor of Gutium who defected to the Persians and became general of the Persian (Medean?) army that overthrew Babylon. The Anchor Bible Dictionary (vol. 2, p. 34) points out that the Babylonians used the word "Gutium" to refer to the Northeast, and the MEDES were in the northeast part of the Persian Empire. The dictionary also mentions that the historian Berossus lists Gutium with the tyrants of the Medes.

There is another possibility -- Gubaru/Gaubaruwa (whom Xenophon the Greek confused with Ugbaru) was also appointed the governor of Babylonia by Cyrus. Other cuneiform texts show that Gubaru continued living for 14 years as governor not only of the city of Babylon but also of the entire region of Babylonia -- as well as of the "Region beyond the River." Gubaru was ruler over a region that extended the full length of the Fertile Crescent, basically the same area as that of the Babylonian Empire. Darius the Mede, we should remember, is spoken of as being "made king over the kingdom of the Chaldeans" (Daniel 9:1), but not as "the king of Persia," the regular form for referring to King Cyrus (Daniel 10:1; Ezra 1:1, 2; 3:7; 4:3). So the region ruled by Gubaru would, at the very least, appear to be the SAME as that ruled over by Darius the Mede. Unless further evidence comes from the histories of the time, it is unclear which of these two individuals is the "Darius the Mede" of the scriptures.

Following the reign of Darius is Cyrus the Persian. Daniel is said to have "prospered during the reign of Darius and the reign of Cyrus the Persian" (Daniel 6:28). Daniel clearly distinguishes between Darius and Cyrus by their race. Darius, a Mede, controlled Babylon until Cyrus, a Persian, took the throne. Daniel also speaks retrospectively of Darius the Mede (Daniel 11:1) in a vision that is set "in the third year of King Cyrus of Persia" (Daniel 10:1).

Therefore, it can be reasonably concluded that Daniel presents the fall of Babylon as occurring at the hands of both the Medes and the Persians. Median rule of Babylon is presented in the form of the historically identifiable Ugbaru or Gubaru, one of whose throne name was probably "Darius the Mede." He was succeeded by the Persian rule of Cyrus the Persian. Thus, from Daniel's record of Babylon's fall, and that of the cuneiform tablets, Media is the empire which succeeded the Babylonian Empire -- not Medo-Persia!

Daniel Vs. the Interpreters

Adherents to the Roman view of the four world empires reject Daniel's conception of an intervening Median Empire, contending that the scenario is not supported by other historical data. According to them, the Median Empire was contemporaneous with the Babylonian Empire and both empires fell to the Persian Empire -- the former in 468 B.C. and the latter in 457 B.C. These interpreters therefore argue that it is incorrect to interject Median control of Babylon between the reigns of Belshazzar and Cyrus since Media was already incorporated into the Persian Empire at the fall of Babylon. H.H. Rowley, however, points out that it is Daniel, not the book's interpreter, who distinguishes between Median and Persian control of Babylon. He explains:

"Thus, it is argued that it is an historical error to suppose that a Median kingdom intervened between the fall of Babylon and the reign of Cyrus, and that we have no right to father on to the author of the book of Daniel so grave an error [supposedly] in the interests of our theory. It is he [Daniel] who states that Darius the Mede succeeded Belshazzar, and who elsewhere speaks of "Darius the son of Ahasuerus, of the seed of the Medes, which was made king over the realm of the Chaldaeans." It is he who says that Daniel prospered "in the reign of Darius, and in the reign of Cyrus the Persian." It is he who represents one as coming to Daniel in a vision which he saw in the third year of Cyrus, king of Persia, and speaking to him retrospectively of the first year of Darius the Mede. It is therefore he who distinguishes between the race of Darius and that of Cyrus, and who sets a Median control of Babylon between Belshazzar and the Persian rule, and the principle that the visions are to be interpreted by the view of the course of history which the author reveals elsewhere in his book leads unmistakably to the identification of the second empire with the Median" (Darius the Mede and the Four World Empires in the Book of Daniel, pp. 147-148).

The kingdom of Belshazzar was followed by the kingdom that was divided between the Medes and Persians. Darius the Mede received the kingdom for an unspecified length of time (i.e., Median control). His rule was followed by that of Cyrus of Persia (i.e., Persian control). These empires are distinguished as separate kingdoms in the unequal horns of the ram, and a distinction is made between the Medes and the Persians throughout the book of Daniel. Therefore it is clear that Daniel intended for the Median kingdom to be recognized as the second of the four world empires.

Jeremiah's Prophecies Against Babylon

Based on Daniel's view of power transfer, from Babylon to Media to Persia, it seems evident that he used the Old Testament writings to buttress the visions he experienced. More specifically, the book of Jeremiah, which predicts Babylon's destruction at the hands of the Medes, clearly influenced Daniel's work.

"In the first year of Darius the son of Assuerus, of the seed of the Medes, who reigned over the kingdom of the Chaldeans, I Daniel, understood BY BOOKS the number of the years which was the word of the LORD to the prophet Jeremias, even seventy years for the accomplishment of the desolation of Jerusalem" (Daniel 9:1-2, The Septuagint).

Daniel says there were "books" which contained the writings of the prophet Jeremiah. Also, these prophecies were "the word of the LORD" concerning the "seventy years" of Babylonian captivity, and were "perceived," or studied, by Daniel. From these two verses, it is obvious that Daniel was familiar with the prophecies of Jeremiah -- especially those relating to the Babylonian captivity. Further, from his statement that Jeremiah was transmitting the "word of the LORD," it may also be concluded that Daniel relied on these "books" as an historical source. Jeremiah is very specific in his prophecy against Babylon. A total and complete destruction of the city is predicted in 50:8-46, a passage too long to quote and, in chapter 51, he repeats the prophecy even more graphically and clearly identifies the MEDES as the instrument of YEHOVAH's anger against Babylon --

"Make the arrows bright! Gather the shields! The LORD has raised up the spirit of the kings of the Medes. For his plan is against Babylon to destroy it, because it is the vengeance of the LORD, the vengeance for his temple" (Jeremiah 51:11, NKJV).

"Prepare against her [Babylon] the nations, with the kings of the Medes, its governors and all its rulers, all the land of his dominion. And the land will tremble and sorrow; for every purpose of the LORD shall be performed against Babylon, to make the land of Babylon a desolation without inhabitant " (Jeremiah 51:28-29, NKJV).

Jeremiah prophesies Babylon's complete destruction at the hands of the "kings of the Medes," and "every land under their dominion." Jeremiah's railings against Babylon (Jeremiah 50; 51) make no mention of the great Persian Empire as a conqueror of Babylon. Jeremiah specifically refers to the Medes.

In Daniel 9:2, Jeremiah is cited as having recorded the "word of the LORD," therefore, there could be no questioning of this "word," delivered by the great prophet Jeremiah, prophesying Babylon's fall to the Medes -- not the Persians!

Isaiah Also Prophesies Median Destruction

The book of Isaiah also prophesies that "the Medes" will destroy Babylon, thereby providing Daniel with a corresponding historical source. Further, it can be demonstrated that Isaiah's depiction of the Medes corresponds to the symbolic portrayal of Daniel's second empire. Isaiah's "burden" against Babylon begins at chapter 13, where he launches into a condemnation of the Babylonian threat to Israel. "The day of YEHOVAH is at hand," he proclaims. "It will come as a destruction from the Almighty" (v. 6). Beginning at verse 17, he identifies the MEDES as the instrument that YEHOVAH God would use to bring about Babylon's destruction --

"Everyone who is found will be thrust through, and everyone who is captured will fall by the sword. Their infants will be dashed to pieces before their eyes, and their houses will be plundered, and their wives taken. Indeed, I am stirring up the Medes against them [the Babylonians], people who have no regard for silver and no pleasure in gold. Their bows will destroy the youth, and on infants they will have no pity, and their eyes will have no compassion on children. Babylon, the glory of kingdoms, the beauty and pride of the Chaldeans, will be like Sodom and Gomorrah when God overthrew them. It will never again be inhabited; it will not be lived in from generation to generation. Arabs will not pitch tents there; shepherds will not make their flocks lie down there. Rather wild creatures will lie down there, and their houses will be full of jackal. Ostriches will live there, and wild goats will dance there. Wolves will howl in their towers and jackals in their luxurious palaces. Its time is drawing near, and its days will not be drawn out any further" (Isaiah 13:15-22, The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible).

This was obviously a prophecy predicting a complete and permanent destruction of Babylon. The prediction was that the destruction was imminent ("time is drawing near," v. 22) and that the destruction WOULD BE ACCOMPLISHED BY THE MEDES ("I am stirring up the Medes against them," v. 17).

Isaiah offers a graphic depiction of the Median destruction of Babylon. Isaiah says that anyone caught by the Medes, whom he describes as brutal and merciless, will "fall by the sword"; those captured will be "thrust through"; infants will be "dashed to pieces"; houses "plundered"; and wives "taken."

Then, in Isaiah 21:2, the prophet proclaims --

"A distressing vision is declared to me; the treacherous dealer deals treacherously, and the plunderer plunders. Go up, O Elam! Besiege, O Media! All its sighing I have made to cease" (NKJV).

These portrayals echo the description of Daniel's second beast, which is also fierce and brutal. Daniel's second beast, a bear, is raised up in a striking position. The bear has three ribs "in its mouth, and is told, 'Arise, devour many bodies!"' (Daniel 7:5). Daniel ascribes the same qualities to Babylon's conqueror as Isaiah does to the Medes. The difference is that Isaiah calls the Medes by name, whereas Daniel uses symbolic references.

The Three Ribs

The three ribs in the bear's mouth may be further identified with Isaiah's description of the Medes. Traditionally, interpreters have understood the three ribs to represent nations conquered by the second empire, even though the text does not state, nor does it indicate, that the ribs represent defeated nations." Howard B. Rand, in his Study in Daniel, claims that

"the three ribs, or a translation by Ferrar Fenton, the three tusks in its mouth among its teeth represent the three main systems of human endevour -- political, economic and religious -- which have devoured much flesh in the form of the oppression which follows in their wake" (Merrimac, MA: Destiny Publishers, 1985, p. 179).

Marshall W. Best maintains that

"the three ribs may represent the kingdoms of Babylon, Lydia, and Egypt which were all eventually conquered by this empire" (Through the Prophet's Eye. Enumclaw, WA: WinePress Publishing, 2000, p.56).

Ralph Woodrow also follows this line of reasoning when he states that:

"The mention of "three ribs" in the mouth -- between the teeth where a bear crushes its prey -- is possibly a reference to the fact that Medo-Persia [?] crushed the three provinces that made up the Babylonian kingdom: Babylon, Lydia, and Egypt" (Great Prophecies of the Bible. Riverside, CA: Ralph Woodrow Evangelistic Association, Inc., 1971, p. 135).

H.H. Rowley concludes, however, that "whatever meaning it [the three ribs] had for the author is irrecoverable" (Darius the Mede and the Four World Empires in the Book of Daniel, p. 154). S.R. Driver suggests another approach to determining the meaning of the ribs. He states that

". it is quite possible that the ribs in the creature's mouth are meant simply as an indication of its voracity, and are not intended as an allusion to three particular countries absorbed by the empire which it represents" ("The Book of Daniel" in Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges, p. 82)..

From the standpoint of Driver's suggestion, the ribs in the mouth of the bear may be seen as symbolizing the three groups of Babylonians that Isaiah points to as particularly vulnerable to Median attack. Isaiah says the Medes will:

1) "slaughter young men";

2) "have no mercy on the fruit of the womb (infants, NIV)";

3) "not pity children."

It is thus reasonable to conclude that the young men, infants, and children devoured by the Medes are represented by the ribs in the mouth of the bear. Said another way, the three ribs in the mouth of the beast represent Median conquest of Babylon. While this identification is inconclusive, it is supported by the context of Daniel and corresponds well with Isaiah's portrayal of the Medes, which seems to have greatly influenced Daniel.

Persia Is the Third Kingdom

With the Median Empire having been identified as the second empire, Daniel's third empire logically is Persia. Daniel describes the third empire in Daniel 2 as the "waist and thighs of bronze" (verse 32) that shall "rule over the entire earth" (verse 39). In Daniel 7, the third empire is symbolized by a leopard that has "four wings of a bird on its back and four heads" (verse 6). Conventional interpreters, insisting that Medo-Persia is the second empire, think that Greece is the third empire:

"Correspondence between the Medo-Persian empires of chapter two, symbolized by the breast and arms of silver and the two-horned ram of chapter eight is unmistakable. That ram is specifically said to be "Media and Persia," and the he-goat kingdom of chapter eight, which succeeded it, is said to be Greece. The Bible clearly identifies the third kingdom as Greece" (Daniel and the Latter Days, Robert D. Culver, p.113).

Culver's statement here relies on interpreting the second kingdom as Medo-Persia, which was proven invalid earlier in this article.

Again, the proof text is Daniel 8:20, 21 -- notice! "The ram which you saw, having the two horns -- they [the horns] are the kings of Media and Persia. And the male goat is the kingdom of Greece. The large horn that is between its eyes is the first king [Alexander]" (NKJV).

Interpreters such as Culver also attempt to support their position by pointing out that the "four heads" of the leopard stand for the fourfold division of Alexander's Greek Empire. But there is no indication in the text, other than in the coincidental use of the number four, that the four heads represent Greek subdivision. It is worth noting that in texts which address this division (Daniel 8:8, 22; 11:4), Alexander himself is first identified, then the division of his kingdom is described. The heads of the leopard indicate no such transition of power.

Rather, the four heads of the leopard may be identified with kings of the Persian Empire -- Cyrus, Cambyses II, Darius Hystaspes and Xerxes. While Cambyses is not mentioned in the Bible, the other three are.

Some scholars, including Porteous, understand the four heads to represent "the extension of the Persian Empire in all directions," and the four wings "swiftness."

The Artaxerxes mentioned in Ezra and Nehemiah has often been considered to be a king who followed after Xerxes, however there is much evidence to indicate that Artaxerxes and Xerxes were one and the same king!

In the ruins of Persepolis can be found reliefs of the “three” kings of the Persian dynasty who were involved with building the city -- Darius I, Xerxes and Artaxerxes. While the faces on the reliefs have been chiseled off, other parts of the reliefs can be used to make our point. It’s very subtle, but nonetheless conclusive -- it’s the famous hand of Artaxerxes! Artaxerxes right hand was LONGER than his left one, and this was so unusual it became his trademark and hence the name “Artaxerxes LONGIMANUS (longimanus is Latin for “long hand”).

A very famous relief at Persepolis showing Darius seated on the throne followed by his son “Xerxes” shows Xerxes with his right hand turned vertically in order to show off his hand for all to see. The hand was carved with great detail showing all the palm creases, etc. You will notice, by comparison, that it is clearly LONGER THAN HIS LEFT! It is because of this unusual hand that Xerxes later became known as “Artaxerxes Longimanus” -- after changing his name locally to Artaxerxes upon becoming king of Persia. This was a common practice among the Persian kings.

The Achaemenids

The Persian Empire -- founded by Cyrus -- is known to historians as the empire of the Achaemenids. According to Wikipedia,

"the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE), known as THE FIRST PERSIAN EMPIRE, was the successor state of the Median Empire, expanding to eventually rule over significant portions of the ancient world which at around 500 BCE stretched from the Indus Valley in the east, to Thrace and Macedon on the northeastern border of Greece. The Achaemenid Empire would eventually control Egypt, unified by a complex network of roads and, ruled by monarchs, to become the greatest empire the world had yet seen."

Continuing, Wikipedia states --

"At the height of its power after the conquest of Egypt, the empire encompassed approximately 8 million km2 spanning three continents: Asia, Africa and Europe. At its greatest extent, the empire included the modern territories of Iran, Turkey, parts of Central Asia, Pakistan, Thrace and Macedonia, much of the Black Sea coastal regions, Afghanistan, Iraq, northern Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Israel, Lebanon, Syria, and all significant population centers of ancient Egypt as far as Libya. It is noted in Western history as the antagonistic foe of the Greek city states during the Greco-Persian Wars, for emancipation of slaves including the Jewish people from their Babylonian captivity, and for instituting infrastructures such as a postal system, road systems, and the usage of an official language throughout its territories. The empire had a centralized, bureaucratic administration under the Emperor and a large professional army and civil services, inspiring similar developments in later empires."

The First Persian Empire became unified with a central administration around Pasargadae, erected by Cyrus. The empire ended up conquering and enlarging the Median Empire to include in addition Egypt and Asia Minor.

It was Cyrus and Darius (the Persian) who, by sound and farsighted administrative planning, brilliant military maneuvering -- and a humanistic world view -- established the greatness of the First Persian Empire and, in less than 30 years, raised them from an obscure tribe to a world power. It was during the reign of Darius that Persepolis was built (518-516 B.C.) and which would serve as the capital for several generations of Achaemenid kings. Ecbatana in Media was greatly expanded during this period and served as the summer capital.

During the reigns of Darius and his son Xerxes it engaged in military conflict with some of the major city-states of Ancient Greece and, although it came close to defeating the Greek army, this war ultimately led to the empire's overthrow.

Darius eventually attacked the Greek mainland but, as a result of his defeat at the Battle of Marathon, he was forced to pull the limits of his empire back to Asia Minor.

Later Xerxes, following his victory at the Battle of Thermopylae, sacked the city of Athens and prepared to meet the Greeks at the strategic Isthmus of Corinth and the Saronic Gulf. In 480 B.C. the Greeks won a decisive victory at the Battle of Salamis and forced Xerxes to retire to Sardis. The army that he left in Greece under Mardonius retook Athens but was eventually destroyed in 479 B.C. at the Battle of Plataea. The final defeat of the Persians at Mycale encouraged the Greek cities of Asia to revolt -- and marked the end of Persian expansion into Europe.

It is interesting to note that some scholars argue that in the context of history of the Near and Middle East in the first millennium, Alexander the Great can be considered as the "last of the Achaemenids" -- partly because he maintained more or less the same political structure and borders as the previous Achaemenid kings.

Eventually the First Persian Empire began to decay as all empires eventually do. Notes the Encyclopedia Britannica:

". the great empire was reduced to immobility and stagnation -- a process which was assisted by the deteriorating influences of civilization and world-domination upon the character of the ruling race. True, the Persians continued to produce brave and honorable men. But the influences of the harem, the eunuchs, and similar court officials, made appalling progress, and men of energy began to find the temptations of power stronger than their patriotism and devotion to the king" (1943, vol. 17, p. 572).

The encyclopedia goes on to state --

"The upshot of these conditions was, that the empire never again undertook an important enterprise, but neglected more and more its great civilizing mission. All the more clearly, then, was the inner weakness of the empire revealed by the revolts of the satraps. These were facilitated by the custom -- quite contrary to the original imperial organization -- which entrusted the provincial military commands to the satraps, who began to receive great masses of Greek mercenaries into their service" (ibid.).

"The Persian Empire," writes J.B. Bury, "was weak and loosely knit, and it was governed by a feeble monarch. and. on the western side, rent and riven by revolts. Persia was behind the age in the art of warfare. She had not kept pace with the military developments in Greece during the last fifty years, and, though she could pay Greek mercenaries, and though these formed in fact a valuable part of her army, they could have no effect on the general character of the tactics of an oriental host. The Persian commanders had no notion of studying the tactics of their enemy and seeking new methods of encountering them. They had no idea of shaping strategic plans of their own; they simply waited on the movements of the enemy. They trusted, as they had always trusted, with perfect simplicity, in numbers, individual bravery, and scythe-armed chariots. The only lesson which the day of Cunaxa had taught them was to hire mercenary Greeks" (A History of Greece to the Death of Alexander the Great, The Modern Library, Random House, Inc., N.Y.).

The Empire of Alexander the Great

It was into this environment of stagnation and decay that a man of unusual ability stepped. A new power arose created by Philip of Macedon. Philip's initial goal was the expansion of Macedon at the expense of Thrace and Illyria and the subjection of the Balkan peninsula. Philip had no ingrained ambition to take on the Persian Empire but, with his assassination in 336 B.C. there was a fundamental change in tactics. In the person of his son, the throne was occupied by a soldier and statesman of genius, saturated with Greek culture and Greek thought -- and intolerant of every goal but the highest. Notes the Encyclopedia Britannica --

"To conquer the whole world for Hellenic civilization by the aid of Macedonian spears, and to reduce the whole earth to unity, was the task that this heir of Heracles and Achilles saw before him. This idea of universal conquest was with him a conception much stronger developed than that which had inspired the Achaemenid rulers, and he entered on the project with full consciousness in the strictest sense of the phrase. In fact, if we are to understand Alexander aright, it is fatal to forget that he was overtaken by death, not at the end of his career, but at the beginning, at the age of 33" (1943, vol. 17, p. 573).

His original ambition of conquest was afterwards merged into a second and larger scheme -- of which he had no conception when he burst forth from Macedonia. This was because Alexander didn't have the requisite geographical knowledge of central Asia. But, in the first instance, his purpose was to conquer the Persian kingdom, to dethrone the king and take his place, to do unto Persia what Persia under Xerxes had done to Macedonia and Greece.

According to Wikipedia,

"Alexander the Great (Alexander III of Macedon) defeated the Persian armies at Granicus (334 BCE), followed by Issus (333 BCE), and lastly at Gaugamela (331 BCE). Afterwards he marched on Susa and Persepolis which surrended in early 330 BCE."

Following Alexander's invasion of Persia nothing really changed regarding the governing structure of the empire. In fact, Alexander regarded himself as the legitimate head of the Persian Empire and, as a result, adopted the dress and ceremonial of the Persian kings. We read in A History of Greece:

"The Persian lords and satraps who submit are received with favor and confidence; Alexander learns to know and appreciate the fine qualities of the Iranian noblemen. Some of the eastern provinces are entrusted to Persian satraps, for example Babylonia to Mazaeus, and the court of Alexander ceases to be purely European. With oriental courtiers, the forms of an oriental court are also gradually introduced; the Asiatics prostrate themselves before the lord of Asia; and presently Alexander adopts the dress of a Persian king at court ceremonies, in order to appear less a foreigner in the eyes of his eastern subjects" (J.B. Bury, The Modern Library, N.Y. p. 771).

In Babylonia Alexander followed an enlightened policy that he had previously followed in Egypt. He set himself up as the protector of the national religions that had been depressed and slighted by the fire-worshipping Persians, and he rebuilt the Babylonian temples that had been destroyed. Above all, he commanded the restoration of the huge temple of Bel that stood on eight towers -- the temple upon which Xerxes had vented his rage when he returned from his defeat at Salamis. Alexander retained the Persian Mazaeus in his post as satrap of Babylonia.

In effect, nothing much changed in the administration and every-day affairs of the Persian Empire. Despite having succeeded to conquer the whole of the Persian Empire, Alexander was unable to offer a stable alternative.

Alexander's empire only lasted eleven years, and after his death on June 13, 323 B.C., the unity of the realm -- which was an essential part of Alexander's conception -- disappeared and the once massive Persian Empire was broken up and succeeded by a few smaller empires -- the most significant of which was the Seleucid Empire ruled by one of his generals.

The Seleucid and Parthian Empires

Alexander conquered the Achaemenid or First Persian Empire within a short time-frame and died young -- leaving an expansive empire of partly Hellenized culture without an adult heir. The empire was placed under the authority of a regent in the person of Perdiccas in 323 B.C., and the territories were divided between Alexander's generals who thereby became satraps after the Persian fashion. Seleucus, who had been "Commander-in-Chief of the camp" under Perdiccas since 323 B.C. (and who helped to assassinate him later) received Babylonia.

Seleucus established himself in Babylon in 312 B.C., and this is used as the foundation date of the Seleucid Empire. He not only ruled over Babylonia, but also the eastern part of Alexander's empire.

After the death of Seleucus, his son Antiochus I reigned from 281-261 B.C. -- to be followed by Antiochus II Theos who reigned from 261-246 B.C. Toward the end of Antiochus II's reign, a number of provinces simultaneously asserted their independence, such as Bactris, Cappadocia and Parthia under a Parthian tribal chief called Arsaces. The Seleucid satrap of Parthia, by the name of Andragoras, first claimed independence at the same time as the succession of his Bactrian neighbor. Soon after, however, Arsaces took over the Parthian territory around 238 B.C. to form the Arsacid Dynasty -- the starting point of the Parthian Empire.

After the death of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the Seleucid Empire became increasingly unstable. Frequent civil wars made central authority tenuous at best. Meanwhile, the decay of the empire's territorial possessions continued apace. By 143 B.C. the Jews -- in the form of the Maccabees -- had fully established their independence and Parthian expansion continued as well.

Mithridates I of Parthia (c. 171-138 B.C.) greatly expanded the empire by seizing Media and Mesopotamia from the Seleucids, and eventually the Parthian Empire stretched from the northern reaches of the Euphrates River to eastern Iran. Notes Wikipedia --

"The Parthians largely adopted the art, architecture, religious beliefs, and royal insignia of their culturally heterogeneous empire. For about the first half of its existence, the Arsacid court adopted elements of Greek culture, though it eventually saw a gradual revival of Iranian [Persian] traditions. The Arsacid rulers were titled the "King of Kings," as a claim to be the heirs to the Achaemenid Empire; indeed, they accepted many local kings as vassals where the Achaemenids would have had centrally appointed, albeit largely autonomous, satraps."

The Wikipedia goes on to say:

"With the expansion of Arsacid power, the seat of central government shifted from Nisa, Turkmenistan to Ctesiphon along the Tigris (south of modern Baghdad, Iraq), although several other sites also served as capitals."

The Encyclopedia Britannica also focuses on this apparent emulation of Persian traits in the Parthian administration -- notice!

"The Parthia Empire, as founded by the conquests of Mithridates I and restored, once by Mithridates II and again by Phraates III, was, to all exterior appearances, A CONTINUATION OF THE ACHAEMENID [FIRST PERSIAN EMPIRE] DOMINION. Thus the Arsacids now began to assume the old title 'King of Kings' [the shahanshah of pre-Khomeini Iran], though previously their coins, as a rule, had borne only the legend 'great king.' The official version, preserved by Arrian in his Parthica (ap. Phot. cod. 58: see Parthia), derives the lines of these chieftains of the Parthian nomads from Artaxerxes II [of the First Persian Empire]" (1943, vol. 17, p. 576).

The encyclopedia goes on to say:

"Although Arsacids are strangers to any deep religious interest (in contrast to the Achaemenids and Sassanids),THEY ACKNOWLEDGE THE PERSIAN GODS and the leading tenets of Zoroastrianism. they perpetuate the traditions of the Achaemenid empire. The Arsacids assume the title 'king of kings' and derive their line from Artaxerxes II. Further, the royal apotheosis, so common among them and recurring under the Sassanids, is probably not so much of Greek origin as a development of Iranian [Persian] views. This gradual Iranianization of the Parthian empire is shown by the fact that the subsequent Iranian [Persian] traditions, and Firdousi in particular, apply the name of the 'Parthia' magnates (Pahlavan) to the glorious heroes of the legendary epoch. Consequently, also, the language and writing of the Parthian period, which are retained under the Sassanids, received the name Pahlavi, i.e., 'Parthian.' The script was derived from the Aramaic" (ibid., p. 578).

The Parthian magnates -- along with the army -- would have little to do with Greek culture and Greek modes of life, which they contemptuously regarded as effeminate and unmanly. They required of their rulers that they should live in the fashion of their country, practice arms and the chase, and appear as Persian sultans -- not as Grecian kings!

These tendencies, however, taken together explain the radical weakness of the Parthian Empire. It was easy enough to collect a great army and achieve a great victory; it was absolutely impossible to hold the army together for any longer period -- or to conduct a regular campaign. While emulating certain aspects of the First Persian Empire in their court and administration, the Parthians proved incapable of creating a firm, united organization such as the First Persian Empire before them and the Second Persian Empire after them gave to their empires.

The Parthian kings themselves were toys in the hands of the magnates and the army who were utterly indifferent to the person of the individual Arsacid. At any moment they were ready to overthrow the reigning monarch and to seat another on his throne. The kings, for their part, sought protection in craft, treachery and cruelty -- and only succeeded in aggravating the situation. These conditions were the same as subsequently obtained under Daniel's fourth empire -- the Islamic caliphate and the empire of the Ottomans.

In time the Parthian Empire was further weakened by internal strife and wars with Rome. That the Arsacid empire should have endured some 350 years after its foundation was a result -- not of internal strength -- but of chance working in its external development. It might well have existed for centuries more, but under Artabanus IV the catastrophe came.

Writes Wikipedia --

". the Parthian Empire. was soon to be replaced by the Sassanid [Second Persian] Empire. Indeed shortly afterward, Ardashir I, the local Iranian ruler of Persis (modern Fars Province, Iran) from Estakhr began subjugating the surrounding territories in defiance of Arsacid rule. He confronts Artabanus IV in battle on 28 April 224 A.D. defeating him and establishing the Sassanid Empire. The Sassanians would not only assume Parthia's legacy as Rome's nemesis, but they would also attempt to restore the boundaries of the Achaemenid Empire. "

One of the common threads in all of the empires that ruled after the collapse of the First Persian Empire was that they all tried to emulate the Persian court and central government.

The Second Persian Empire (Sassanid)

| Map of Second Persian Empire |

Conflicting accounts shroud the details of the fall of the Parthian Empire and the subsequent rise of the Sassanid Empire in mystery. Ardashir I (a descendant of a line of the priests of the goddess Anahita) established the second phase of the Persian Empire in Istakhr after the fall of the Arsacid Empire and the defeat of the last Arsacid king, Artabanus IV.

Factors that aided the rise to supremacy of the Sassanids were the Artabanus-Vologases dynastic struggle for the Parthian throne, which more than likely allowed Ardashir to consolidate his authority in the south with little or no interference from the Parthians; and the geography of the Fars province, which separated it from the rest of Iran. Crowned in 224 at Ctesiphon as the sole ruler of Persia, Ardashir took the title Shahanshah -- or "King of kings." This brought the 400-year-old Parthian Empire to a close and marked the beginning of four centuries of Sassanid rule.

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica:

"The new empire founded by Ardashir I -- the Sassanid, or Neo-Persian empire -- is essentially different from that of his Arsacid predecessors. It is, rather, a CONTINUATION OF THE ACHAEMENID TRADITIONS which were still alive on their native soil. Consequently the national impetus -- already clearly revealed in the title of the new sovereign -- again becomes strikingly manifest. The Sassanian empire, in fact, is ONCE MORE a national Persian or Iranian empire" (Vol. 17, article "Persia." 1943).

Shapur I -- the son of Ardashir I -- assumed the title "King of kings of the Iranians and non-Iranians" -- thus emphasizing his claim to WORLD DOMINATION. His successors retained the designation, little as it corresponded to the facts, for the single non-Iranian land governed by the Sassanids was the district of the Tigris and Euphrates as far as the Mesopotamian desert.

Historians have divided the second phase of the Persian Empire into a number of eras, such as --

1) First Golden Era (309-379)

Following the death of Hormizd II, pre-Islamic Arabs from the south started to ravage and plunder the southern cities of the empire -- even attacking the province of Fars, the birthplace of the Sassanid kings. Shapur II led a small but disciplined army south against the Arabs whom he defeated, securing the southern areas of the empire. Following this he started his first campaign against the Romans in the west. During Shapur's second campaign against the Romans in 359, he succeeded in retaking Singara and Amida. In response to this the Roman emperor Julian struck deep into Persian territory and defeated Shapur's forces at Ctesiphon, but having failed to take the Persian capital, he was killed while trying to retreat back to Roman territory. His successor -- Jovian -- trapped on the east bank of the Tigris, had to agree to hand over all the provinces which the Persians had ceded to Rome in 298 (as well as Nisibis and Singara) in order to secure safe passage for his army out of Persia.

Shapur II pursued a harsh religious policy throughout his empire. Under his reign, the collection of the Avesta, the sacred texts of Zoroastrianism, was complied. Heresy and apostasy were punished and Christians were persecuted. The latter was a reaction against the pagan "Christianization" of the Roman Empire by Constantine the Great. Shapur II, like Shapur I, was amicable towards the Jews, who lived in relative freedom and gained many advantages during his administration. At the time of Shapur's death, the Persian Empire was stronger than ever -- with its enemies to the east pacified and Armenia under Persian control.

2) Intermediate Era (379-498)

From Shapur II's death until the first coronation of Kavadh I there was a mainly peaceful period with the Romans -- interrupted only by two brief wars, the first in 421-422 and the second in 440. Throughout this time, Sassanid religious policy differed dramatically from king to king. Despite a series of weak leaders, the administrative system established during the reign of Shapur II remained strong, and the empire continued to function effectively.

Yazdegerd I (399-421) has often been compared to Constantine I of the Roman Empire by historians. Much like his Roman counterpart, Yazdegerd I was an opportunist. Like Constantine the Great, Yazdegerd I practiced religious tolerance and provided freedom for the rise of religious minorities. He stopped the persecution against the Christians and even punished nobles and priests who persecuted them. His reign marked a relatively peaceful era. He made lasting peace with the Romans and even took the young Theodosius II (408-450) under his guardianship. He also married a Jewish princess who bore him a son called Narsi.

Yazdegerd II (438-457) was a just, moderate ruler but, in contrast to Yazdegerd I, pursued a harsh policy towards minority religions -- particularly Christianity. During his eastern campaign, Yazdegerd II became suspicious of the Christians in the army and expelled them all from the governing body and the army. He then persecuted the Christians and, to a much lesser degree, the Jews. In order to re-establish Zoroastrianism in Armenia, he crushed an uprising of Armenian Christians at the Battle of Vartanantz in 451. The Armenians, in spite of this, remained primarily Christian.

3) Second Golden Era (498-622)

In 531 Khosrau I (also known as Anushirvan -- "with the immortal soul") ascended to the throne of Persia with his classical name Chosroes. He is the most celebrated of the Sassanid rulers and is most famous for his reforms in the aging governing body of Sassanids. In his reforms, Khosrau I introduced a rational system of taxation based upon a survey of landed possessions -- which his father had begun -- and tried in every way to increase the welfare and the revenue of his empire.

Khosrau I's reign witnessed the rise of the dihqans (literally, village lords) -- the petty landholding nobility who were the backbone of later Sassanid provincial administration and the tax collection system. Khosrau I was a great builder who embellished his capital, founded new towns and constructed new buildings. He rebuilt the canals and restocked the farms destroyed in previous wars. He built strong fortifications at the passes and placed subject tribes in carefully chosen towns on the frontiers to act as guardians against invaders.

He was tolerant of all religions, though he decreed that Zoroastrianism should be the official state religion, and was not unduly disturbed when one of his sons became a Christian.

Following Khosrau I's death, Hormizd took the throne. The war with the Byzantines continued to rage intensely but inconclusively. In 602 Khosrau II used the murder of his benefactor as a pretext to begin a new invasion of the Byzantine Empire -- which met with little effective resistance. Khosrau's generals systematically subdued the heavily fortified frontier cities of Byzantine Mesopotamia and Armenia, laying the foundations for unprecedented expansion of the Persian Empire. The Persians overran Syria and captured Antioch in 611.

In 613, the Persian generals Shahrbaraz and Shahin decisively defeated a major counter-attack outside Antioch, led by the Byzantine emperor Heraclius. Thereafter, THE PERSIAN ADVANCE CONTINUED UNCHECKED. Jerusalem fell in 614, Alexandria in 619 and the rest of Egypt by 621. THE SASSANID DREAM OF RESTORING THE ACHAEMENID BOUNDARIES WAS CLOSE TO COMPLETION. This remarkable PEAK OF EXPANSION was paralleled by a blossoming of Persian art, music and architecture. The Byzantine Empire was on the verge of collapse and the borders of the Achaemenid Empire came close to being restored on all fronts.

4) Decline and Fall (622-651)

Starting during the Second Golden Era, the 100-years' struggle between Byzantine Rome and Persia ended in 627. This struggle utterly enfeebled both empires and consumed their powers. "In the spring of 632," explains Wikipedia, "a grandson of Khosran I who had lived in hiding, Yazdegerd III, ascended the throne. The same year, the first raiders from the Arab tribes, NEWLY UNITED BY ISLAM, arrived in Persian territory. Years of warfare had exhausted both the Byzantines and the Persians. The Sassanids were further weakened by economic decline, heavy taxation, religious unrest, rigid social stratification, the increasing power of the provincial landholders, and a rapid turnover of rulers. THESE FACTORS FACILITATED THE ISLAMIC CONQUEST OF PERSIA."

In the same year that saw the coronation of Yazdegerd III -- the beginning of 633 -- the first Islamic squadrons made their way into Persian territory. After several encounters there ensued (637) the battle of Kadisiya (Qadisiya, Cadesia), fought on one of the Euphrates canals, where the fate of the Sassanid Empire was decided. A little previously (in August of 636) Syria had fallen in a battle on the Yarmuk (Hieromax), and in 639 the Islamic forces penetrated into Egypt.

Under the Caliph 'Umar ibn al-Khattab, a Muslim army defeated a larger Persian force led by general Rostam Farrokhzad at the plains of al-Qadisiyyah and besieged Ctesiphon. Ctesiphon fell after a prolonged siege and Yazdegerd fled eastward from Ctesiphon, leaving behind him most of the empire's vast treasury. The fall of Ctesiphon left the Sassanid government strapped for funds with the Islamists acquiring a powerful financial resource for their own use. Yazdegerd's generals tried to organize a resistance in Media but were defeated at the battle of Nehavend (641). After hearing of the defeat Yazdegerd, along with most of the Persian nobility, fled further inland to the eastern province of Khorasan. There he was assassinated in the city of Merv in late 651.

This ended the SECOND PHASE of the Persian Empire -- the THIRD KINGDOM of Daniel 2. The Sassanid Empire ended no less precipitately and ingloriously than that of the Achaemenids. Its abrupt fall was completed within a period of five years and most of its territory absorbed into the Islamic caliphate. By 650 the Muslims had occupied every province to Balkh and the Oxus. Only in the secluded districts of northern Media (Tabaristan) the "generals" of the house of Karen (Spahpat, Ispehbed) maintained themselves for a century as vassals of the caliphs.

The fall of Daniel's third kingdom sealed the fate of its religion. The Muslims officially tolerated the Zoroastrian creed, though occasional persecutions were not lacking. But little by little it vanished from Iran, with the exception of a few remnants, the faithful finding refuge in India at Bombay.

Since Media is easily recognizable as the second kingdom, identification of the third kingdom as Persia does not depend on a positive identification of the leopard's four heads in Daniel 7. Such an effort, while it might be intriguing, would, nevertheless, produce an inconclusive result. It has already been established that Media is the second kingdom, and it will be shown in another article that Islam is Daniel's fourth kingdom. By this sort of backdoor approach we can prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that the identity of the third kingdom is Persia. The separate, but allied, kingdoms of Media and Persia are, respectively, the second and third empires of Daniel.