In 1868 and 1869 six pioneering women arrived in the rough and tumble town of Laramie, Wyoming Territory. Some were married, some single and they included businesswomen and teachers.

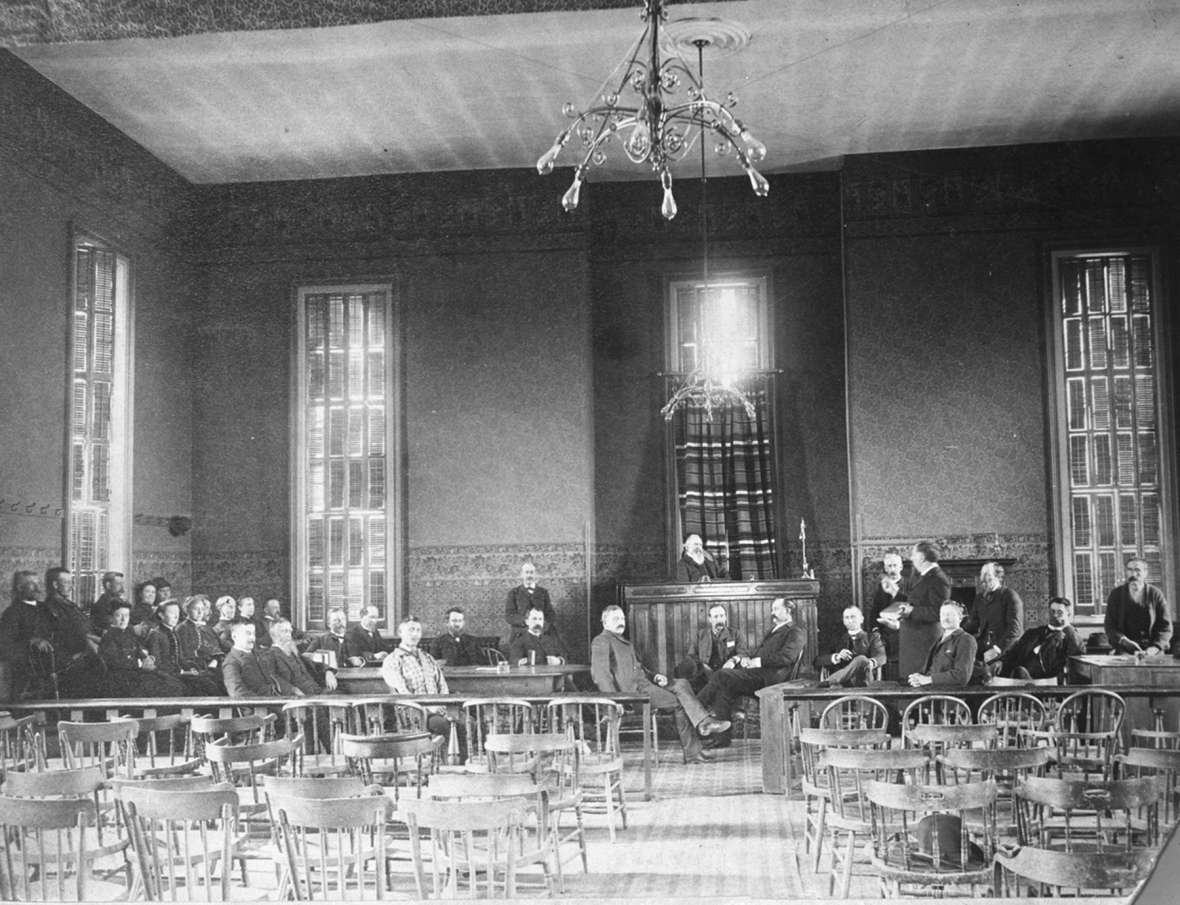

Little did they know that in 1870 they would make world history. In the wake of the first Territorial Legislature’s 1869 suffrage act, they would be called to sit on a formal grand jury of up to nine men and six women, presided over by Judge John Howe. A grand jury has the power to investigate potentially criminal conduct and decides whether criminal charges should be brought against a defendant or group of defendants. Women had never served on grand juries or trial juries before.

The first woman jurors, and their bailiff

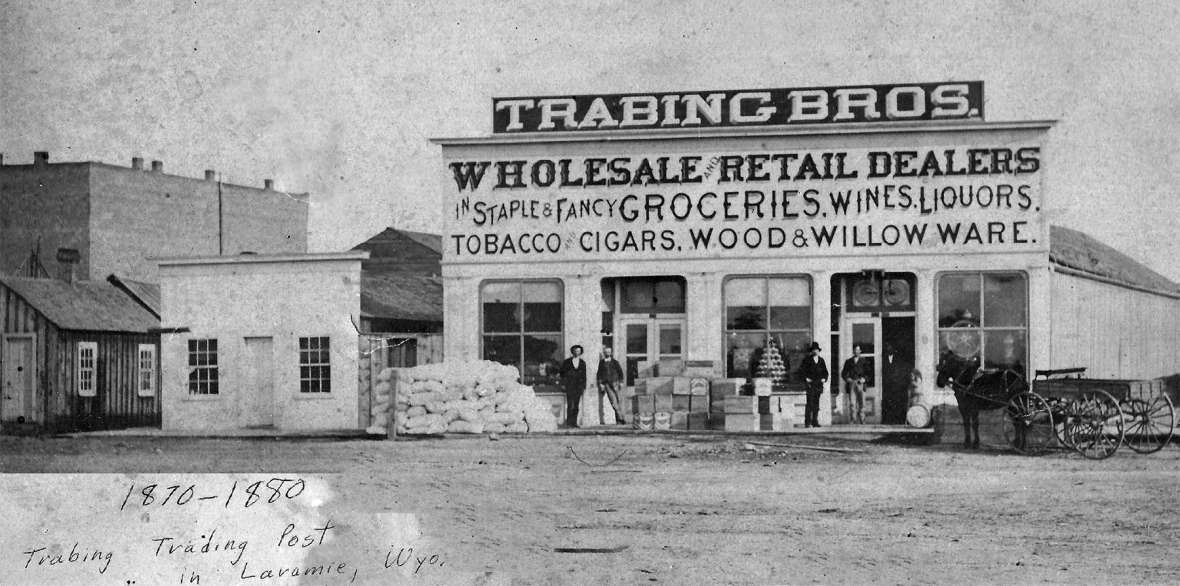

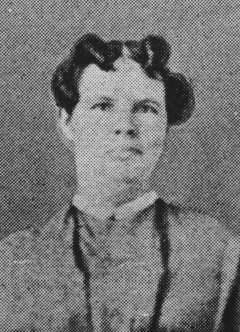

The women came from all walks of life. The first chosen was Eliza Stewart. Born in Pennsylvania in 1835, she graduated from Washington Female Seminary in Washington, Pa., as class valedictorian. For the next eight years, she taught school in her native Crawford County, Pa. Arriving as a 35-year-old single woman in December 1868, she was employed as the first schoolteacher in Laramie. Soon after she completed her jury duty, she married Stephen Boyd. Eliza would serve on a jury again in 1871.

|

Amelia Hatcher (later Heath) was born in England in 1842 of Scottish parents. The 1870 census shows that she was in Laramie and living in the house of her father Robert Galbraith with her 8-year-old son, also named Robert. She moved to Laramie after the death of her first husband. She was an independent businesswoman, running a millinery shop in downtown.

Mary Jane Mackle was born in New York City on Christmas Day, 1847. She was the wife of a clerk at Fort Sanders near Laramie, Joseph Mackle, whom she married in 1862 at Leavenworth, Kan. around age 15. Little is known about the Mackles as they moved from Laramie in 1873.

Jane Hilton was born in 1829 in New York. In 1870 she was living with her husband George F. Hilton and daughter Nellie Hilton in Laramie. They arrived in 1868 and her husband was a physician and a minister who organized the Methodist church in Laramie. She served again on a grand jury in Laramie in February 1871.

Sarah Pease was born in 1840 and moved to Laramie from Crystal Lake, Ill., in 1869 with her husband Lorenzo Dow Pease, whom she had married in 1867. Mr. Pease was a prominent attorney and judge during his time in Laramie and was deputy clerk of district court. Mrs. Pease later served as Albany County Superintendent of Schools for two terms. She was the only one of the six women who wrote a detailed account of that first jury.

Mrs. Annie Monaghan was born in Ireland in 1845. Although not listed in all reports of the first women on the grand jury, in her very detailed 1889 personal remembrance of the jury, Mrs. Sarah Pease stated that she looked up the court record of the jury proceeding and found Mrs. Monaghan as one of those who served.

Some accounts of the grand jury list Agnes Baker as one of the jurors. She was called but released upon her request and replaced by Sarah Pease.

It was not at all clear that the women wanted to serve. In Pease’s later recollection of the grand jury selection she noted that all the women who were in the jury pool had decided to make up various excuses to avoid serving. But after hearing Judge John Howe skillfully explain what serving would mean to the community, the women consented.

Mrs. Martha Symons Boies (later Atkinson) was selected to act as a bailiff for that same grand jury, the first woman in history to serve in such a judicial position. Mrs. Boies was called upon because one of the cases that the mixed-gender jury was hearing ran very long into the evening and the judge required that they stay overnight in a local hotel. He further ordered that they be provided the protection of a bailiff. Given the sensitivity of women being on a jury, he selected a woman to guard their rooms.

Having married Jeremiah Boies in 1866 after the untimely drowning death of her first husband, Martha arrived in Laramie in a prairie schooner with her children on May 9, 1868, soon after the Union Pacific Railroad had arrived in town. Mr. Boies, a well-known local businessman, died at age 96 in 1900. Martha then married prominent local rancher, James Atkinson, the following year. During her life of almost 87 years, Martha Symons Boies Atkinson crossed an ocean, married three times, raised two sons, served as an assistant to her undertaker husband, managed a boarding house and made a rather large piece in the history of the attainment of full rights for the women of the United States. She died in Laramie March 23, 1917, at her home at Second and University and is buried in Greenhill Cemetery. Her direct descendants, through her son John, have lived in Wyoming for six generations.

Women would also be selected again in Laramie in March and September 1871 and March and July of that year in Cheyenne for both grand and petit—that is, trial—juries.

Why women were called and served

Two reasons have been given for issuing a jury call to the women, and a third seems likely. Judge John Kingman, who assisted Judge Howe in the court session, stated later that women were put into the jury pool by the Albany County Commissioners. Kingman claimed that the commissioners were opposed to female suffrage and if the women served, their service would surely be unsatisfactory and could be used to throw scorn on the 1869 suffrage act.

In her later recollection, Sarah Pease claimed that the women were called because the judges were tired of men not paying attention to the proceedings in the prior session of court and were unwilling to convict their acquaintances. Women, she stated, did not suffer the same shortcomings.

There is yet another plausible reason why the judges let the women serve. Judge Kingman was frequently noted as an ardent supporter of the 1869 suffrage act. He is also credited with assisting in the appointment of Esther Hobart Morris as the first woman justice of the peace. He may have construed the act’s words “to hold office” to include jury duty.

Service opposition

Even before the women chosen could be seated, a challenge arose. Albany County Attorney Stephen Wheeler Downey wrote to Judge Howe five days before the March 7 opening of court asking about the legality of women serving as jurors.

The exact content of the letter is not known but can be deduced from Judge John Kingman’s later remarks on the letter. Kingman later wrote: “At this stage of the case, Col. Downey, the prosecuting attorney for the county, wrote to Judge Howe for advice and direction as to the eligibility of women as jurors, and what course should be taken in the premises.” Downey was informed that the women would be seated.

After the women were called on March 7th, Downey asked the court to exclude the women, despite what he had been told earlier. Justice Howe reiterated his stance and the six women were seated. Downey did this for two possible reasons. Most importantly Downey knew that the same legislature that passed the suffrage act on Dec. 10, 1869, passed a law on Dec. 7 th stating only males were eligible for jury duty. If that was the law, he felt he was obliged to follow it. Less likely was an explanation in a later book by Downey’s daughter Alice, who was only a child when her father died. Alice Downey wrote that her father believed that women should not be exposed to the “grim and unpleasant” duty of serving on a jury. In any case, his challenge was overruled.

Opposition came from other sources as well. Nathan Baker, editor of the influential Cheyenne Leader, railed against women serving when their names were announced on March 1, 1870. Baker offered several specious arguments, including the claim that “the feminine mind is too susceptible to the influence of emotions to allow the supreme control of the reason.”

And when the first indictment the mixed jury reported out as “true” went to trial, defense attorney Melville C. Brown also moved that the women be excluded. The motion was denied. When his client was convicted Brown argued that the conviction should not stand because women were on the jury. That too was overruled, and his client’s conviction stood.

Women barred from serving.

Those multiple rulings by Judge Howe should have settled the question. After he left the bench in October 1871, however, women were excluded from serving under Howe’s replacement as judge of the First District, which at the time included Albany and Laramie Counties. It is not entirely clear why this change occurred. Howe was replaced by Joseph Fisher, a Union Army veteran from Pennsylvania. It is possible that he agreed with Downey’s position that the jury qualification law of Dec. 7th took precedence over the Dec. 10 suffrage act. Moreover, he likely believed those words “hold office” did not apply to jury duty.

There is another possibility. Newspaper articles and Kingman’s statement clearly indicated women were put into the jury pool by county commissioners. There was no voter registration at the time from which to choose potential jurors, so it was up to the commissioners to determine not only which women would be placed in the jury pool but the ratio of men to women. It is possible that the commissioners in Albany and Laramie counties stopped placing women’s names in the pool in late 1871.

Wyoming did not get around to changing jury qualification rules until 1949 and from 1871 to then (with one small exception) women did not serve on juries.

Downey and Brown have a change of heart.

Though opposed to seating women on the jury in 1870, both Downey and Brown, the defense lawyer, would later champion women’s rights and would not challenge women being seated in 1871. Both men would serve in the 1871 Territorial Legislative Assembly when an attempt was made to repeal the 1869 suffrage act.

Downey spoke at length in an effort to thwart the attempt. Initially his efforts fell short when the Assembly passed a repeal act. Governor John Campbell vetoed it. Downey and Brown both voted against the attempted override. Downey’s vote in the upper house was especially important because the override succeeded in the lower house where Brown served. The override failed by one vote in the upper chamber where Downey served, women’s suffrage in Wyoming was preserved and never challenged again.

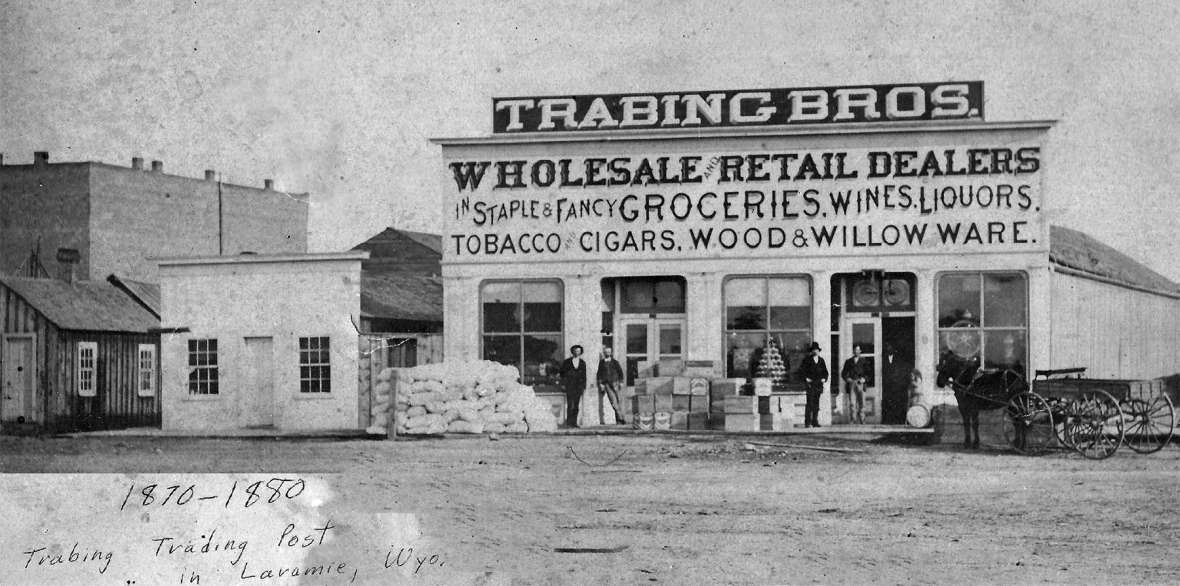

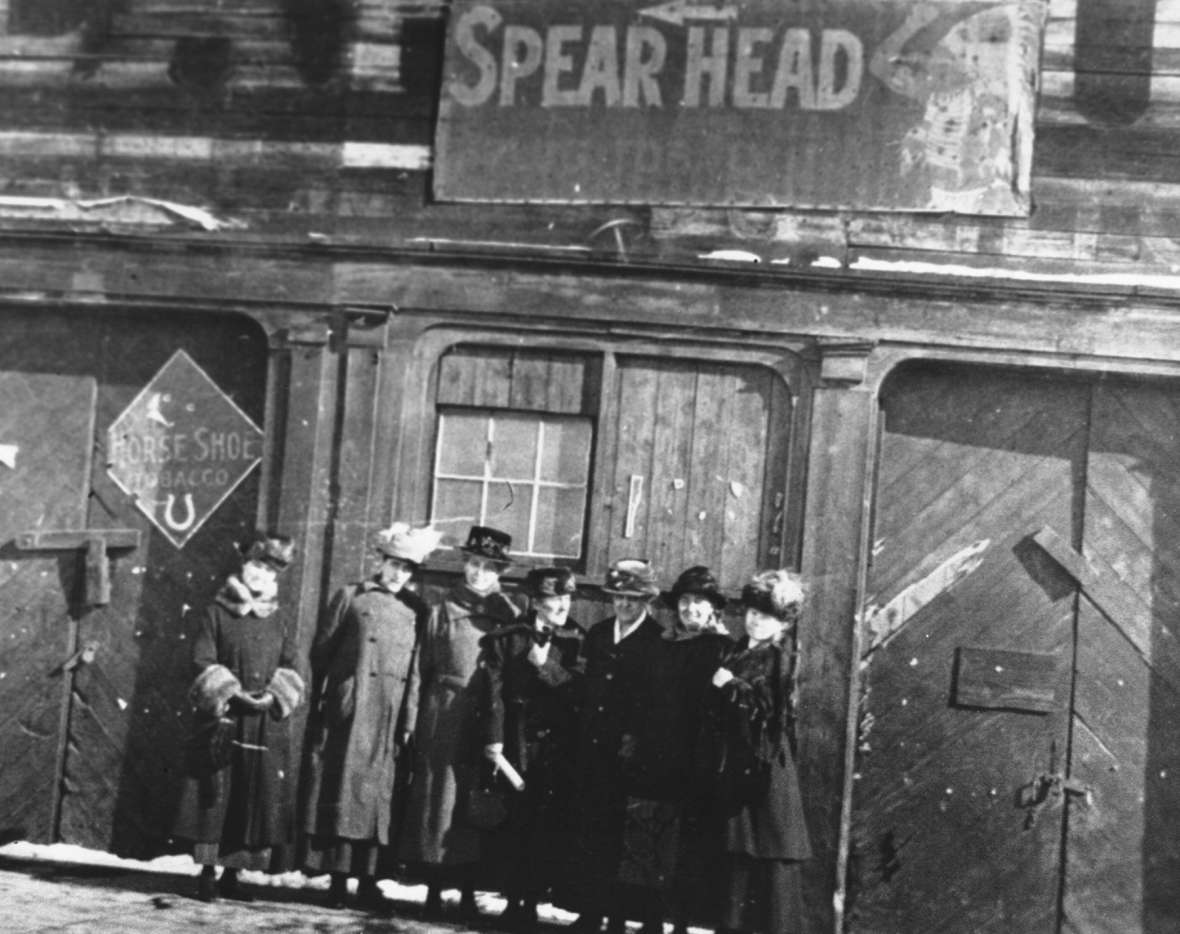

when nationally prominent suffragist Carrie Chapman Catt, third from right, was in Wyoming to lobby for ratification of the 19th Amendment and found a chapter of the new League of Women Voters, local professor and suffragist Grace Raymond Hebard, center, and women in Catt’s party visited the site of the first courtroom where women served on a jury—once the Trabing Brothers store, by then the disused Variety Theater. American Heritage Center" />

when nationally prominent suffragist Carrie Chapman Catt, third from right, was in Wyoming to lobby for ratification of the 19th Amendment and found a chapter of the new League of Women Voters, local professor and suffragist Grace Raymond Hebard, center, and women in Catt’s party visited the site of the first courtroom where women served on a jury—once the Trabing Brothers store, by then the disused Variety Theater. American Heritage Center" />